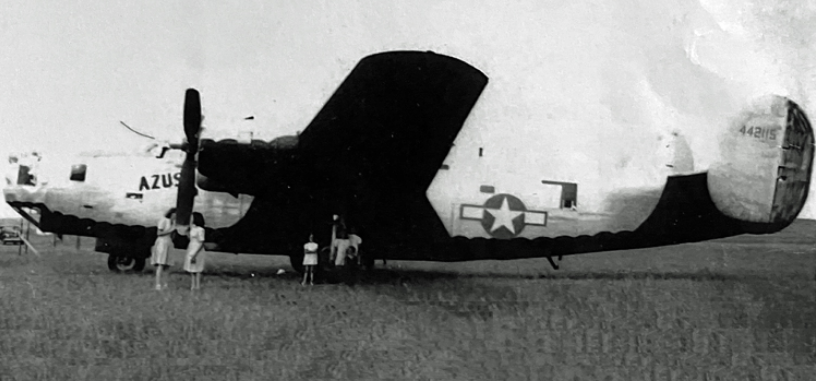

A local paper had an interesting story about World War 2 bomber pilot George Ott. This article speculated that George had flown a B-17 home to New England and that plane became the static display for the locally famous Bomber Club. A few of us in the know including George’s family knew George did not play a part in getting a plane to the Bomber Club. Some of us also knew that the plane at the Bomber Club was not a B-17. I am too young to have seen the plane at the Bomber Club but over the years had heard about it and had been told that the plane was a B-25 twin engine medium bomber. This made sense because a B-25 could have been easily landed in a field north of New England. Occasionally I would hear that the bomber was a B-24 (very large 4 engine plane) and I concluded that this was in error as no one would dare land a plane that size in a field. I concluded that the plane was a B-25 and calling it a B-24 was simply a slip of the tongue. I eventually discovered I was WRONG!

Thanks to Bill Hanson of New England who got me in touch with Wendy, the daughter of the original owner of said “Bomber Club”, George Koppinger. She sent me a copy of a letter written by the pilot who flew the bomber and landed it in a field north of New England. It was indeed a B-24 World War 2 heavy bomber!

Here is the story of how it got there.

Short field landing by Edgar J Allen

While I was with the Sixth Ferry Group in Long Beach, California, I was required to ferry various types of aircraft around the country. These were mostly surplus aircraft being disposed of by the Army Air Force.

One such “opportunity” came on July 3, 1946. I, along with a co-pilot Lt. R. G. Madrid, and engineer T/Sgt B. V. Mullen, received orders to proceed to Mather Field, California, to ferry a B-24 Liberator to Dickinson, ND. The aircraft was to be delivered to Mr. George Koppinger who lived in New England, a town about thirty miles south of Dickinson.

We were flown to Mather field the afternoon of July 3 and it took until almost noon, July 4th to inspect the aircraft and have a number of maintenance problems corrected by the limited maintenance crew available on this holiday.

Since we were restricted to flying the aircraft during daylight hours under visual flight rules, we couldn’t make it all the way to Dickinson on July 4th, so we planned to go as far as Spokane, WA, and then continue to Dickinson the next day. We thought this schedule would work out fine because we reasoned that Mr. Koppinger would be hard to find on the Fourth of July.

We arrived in Dickinson shortly after noon July 5th, and I immediately called Mr. Koppinger in New England.

When I identified myself and stated my purpose, he exploded and shouted angrily, “Where were you yesterday when I needed you?”

I calmed him down and eventually learned why he was so upset. He had planned an air show for July 4th and had distributed many hand bills in that area advertising he’d have a “Giant Liberator Bomber” on display. His air show had fizzled because his main attraction was AWOL. He declared it was now too late to help him and he was not the least bit interested in signing for the aircraft.

That put me in a bind because I had not been told of the requirement to be there in time to support his air show. I was unwilling to face telling my home base I couldn’t deliver the aircraft, so I tried to find a solution to the dilemma. I continued talking with Mr. Koppinger and learned he had a friend who was willing to fly the B-24 into his little field near New England.

That gave me an idea, so I asked him, “If we put the aircraft into your field, will you sign for it then?”

He said he would, so I discussed my plan with Lt. Madrid and Sgt. Mullen and they agreed I could try it. When I asked Mr. Koppinger for details on how to find his field and the conditions of the landing area. I learned the field was nothing more than part of a wheat field and it was less than a half mile long!

We filed a flight plan with the local Civil Aeronautics Authority and took off for New England. When we arrived there, we were unable to locate the field at first, so we circled the town a couple of times hoping to pick it out from all the other wheat fields in the area. We soon saw a clue: A line of cars kicking up dust as they hurried along a dirt road heading north east out of town. We guessed correctly that these folks were headed toward the field where we were expected to attempt a landing. It wasn’t long before we were able to identify the field, and from the small size of it we could understand their desire to be on hand to watch the excitement.

We circled low over the field where the cars were stopping and assessed our chances of making it. On the near end of the field was a barbed wire fence about three feet high strung along a ridge about three more feet high caused by years of plowing to the outside of the field. At the far end was a ditch about three or four feet deep and twelve to fifteen feet across caused by erosion of a small road leading to another field off to the left.

We then made two low passes off to the side of the landing area for a closer inspection for rough spots, holes or whatever. We didn’t see any, so we circled wide, went through the landing check list and began a straight- in approach. We were used to landing on 7,000 to 10,000 foot paved runways and this 2’500 foot, soft, dirt field with obstacles at both ends didn’t look very inviting. I came in as low and slow as I dared, remembering that runway behind our touch-down point was worthless.

At about fifty feet Lt. Madrid shouted unnecessarily, “Don’t hit the fence!” I thought maybe he saw something I didn’t and pulled up just a tiny bit, but we cleared the fence by plenty. As we crossed over the fence, I chopped the power and we started to settle in, but it seemed we were going to float forever. Going around and making another approach flitted through my mind, but then we came to earth with a thud. The ground was speeding swiftly by, and I knew I had to get the brakes on in a hurry, so I slammed the nose down quickly with a crunch and applied full braking. We began kicking up clouds of dust from the dry field. We were all watching the fast approaching ditch at the far end of the field, which wasn’t very far by this time, trying to calculate where we would stop. We were still going at pretty good clip when I determined that our stopping point was going to be in or beyond the ditch. So at the last instant I released the left brake, applied power to both left engines, made a careening turn to the right, kicking up more clouds of dirt and we missed the ditch by just ten feet. We continued around, taxied up in front of the crowd of about a hundred who had gathered to watch the end of our trip.

Mr. Koppinger identified himself and I said to him, “well sir, here is your white elephant.” He asked, “Why do you say that?”, and I replied, “It’ll stay here forever because you’ll never be able to get it out of this field.”

We stayed around for a while answering questions and basking in all the attention we were getting, then Mr. Koppinger took us to town and, to my great relief, cheerfully signed for the aircraft. At that moment I wondered what his attitude would have been if we had damaged the aircraft on landing, because we had not discussed that possibility beforehand.

Later Lt. Madrid and I both agreed that we had gotten away with a very risky and unauthorized undertaking, but our home base never became aware that we had done anything but routinely deliver the aircraft to Mr. Koppinger in Dickinson in accordance with our orders.

Postscript: After setting several years at the Bomber Club being exposed to the elements and steadily deteriorating it must have been sold to a salvage buyer, dismantled and hauled off. Bill Hanson remembers at some point seeing the wings loaded on semi-trailer. The salvage buyer probably didn’t have to pay much for the old plane and it was a lot of work to tear it apart. If that plane was still setting in a field north of New England, even in a deteriorated state, it could well be worth several million dollars!